$1,382.

That’s how much Bianca Garcia’s 8-year-old son spent on microtransactions in Roblox without her permission.

“We had that conversation with him,” Garcia said. “We said, ‘Do you realize this is stealing?’ He just thought he was getting free Robux. He thought he had hacked the system.”

Kids are naive. They don’t know what they’re doing is wrong.

But they aren’t the only ones who are vulnerable to being exploited by microtransactions in video games. Loot boxes. Power-ups. Character skins in games like Fortnite. Microtransactions have always had this sort of pull on gamers. You can’t help but want to spend money on in-game items.

Microtransactions are in-game payments made with real currency in exchange for virtual goods. They became mainstream in 2006, after the action role-playing game The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion released horse armor. Purely a cosmetic item, this horse armor was an optional $2.50 DLC that is credited with starting the microtransaction craze.

But companies are taking advantage of our desire for in-game items, skins and accessories. They are overpricing items knowing that we’ll buy them because they involve our favorite character, or they’re from our favorite series.

Michelle Zelinski is an avid Sims 4 player who used to play a lot of the gacha game Genshin Impact.

“You spend your whole day grinding to maybe get one item, but if you’re employed you don’t want to do that, so you’re like, I’ll use my cash to do it,” she said.

Each year, companies make it harder to get in-game currency to the point where it becomes absurd. “In Genshin, you had to fight tooth and nail to get a 5-star character,” Zelinski said.

It’s not just Genshin Impact either; in many games, it’s challenging to earn loot or a character. But when a challenge becomes a hassle, that’s when it feels like a game is forcing you to spend money.

The point of a free-to-play game is to be accessible to all players, especially those who may not have the finances. When game companies implement these pay-to-win mechanics, they only alienate players.

Sometimes players become obsessed with a game to the point where they spend an unreasonable amount of money on it. Zelinski had this experience when playing Genshin Impact.

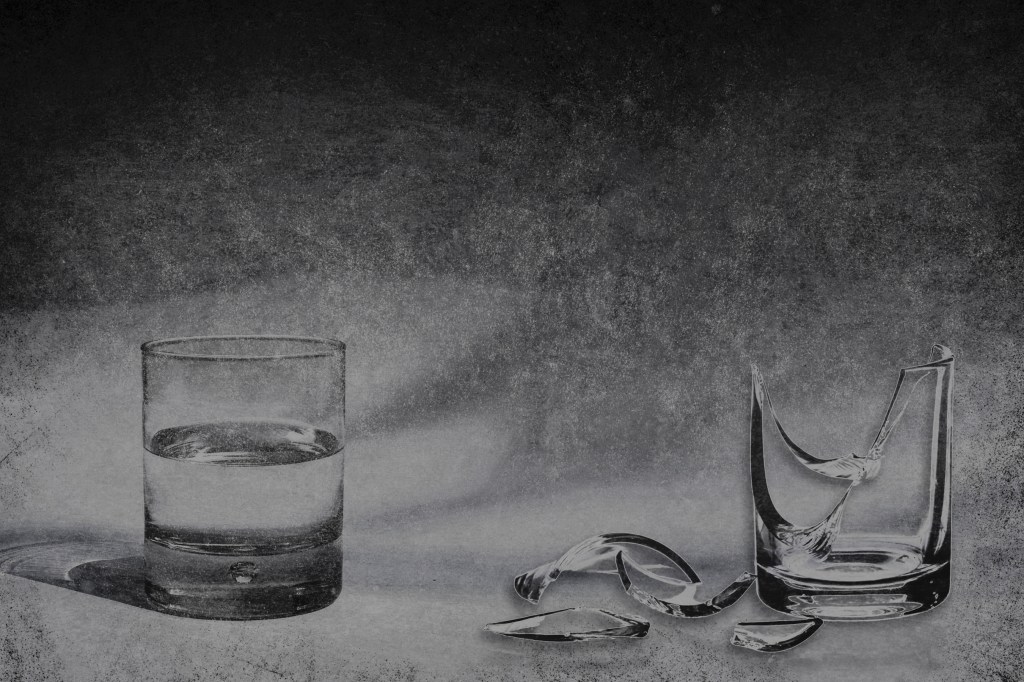

“I believe I spent $400 in total,” she says. “I spent $200 on one character and then $200 on another. Then I sat there and was like, why the fuck did I do that? People are so vulnerable to the idea of easy gambling–gambling lite, almost.”

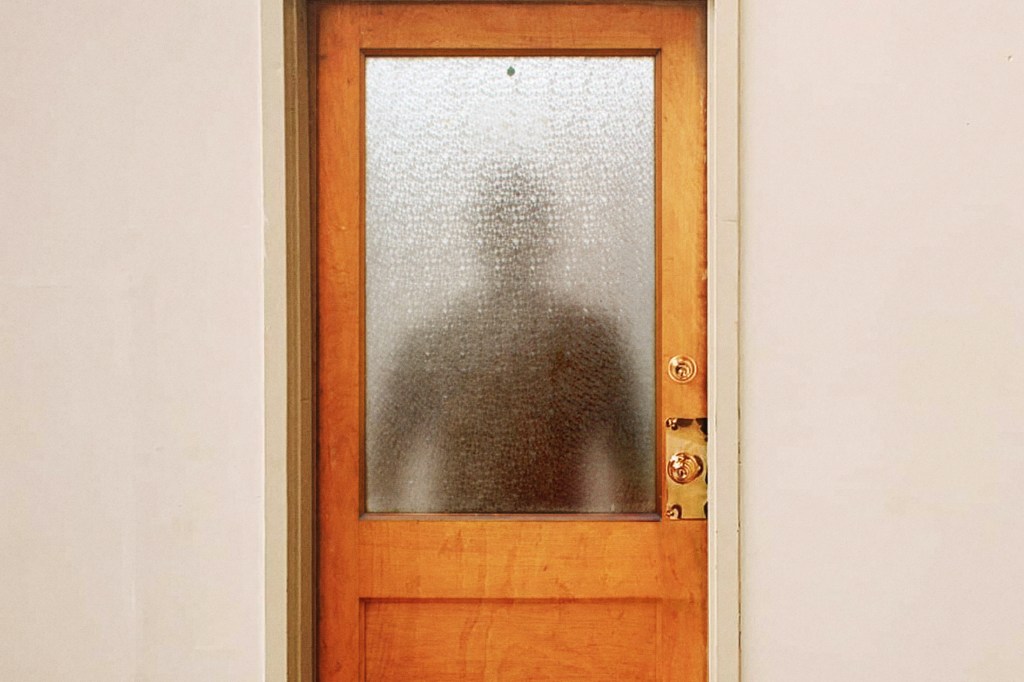

Adults are vulnerable enough, but the fact that children are exposed to these dangers is scary–especially when the games are so easily available, most being free to play.

“It’s just predatory to introduce to children these gambling mechanics when their brain is still developing,” Zelinski said.

Garcia is frustrated that video game companies don’t put any additional safeguards in place to help keep this from happening. After the incident with her son, she was not able to get her money back. PayPal said there was nothing they could do and it was already too late.

“They are benefiting. They are getting the money. I don’t think they care,” she said. “The fact that they shut it down and were like, ‘Nope, we’re not responsible,’ that just hurt.”

At the end of the day, she just wishes companies took more action to stop this from happening.

“When seeing six or seven or eight transactions on my account, a call, an email, something should be done to say, ‘Hey, is this really you?” Garcia said.

From the companies’ perspective, the argument is that without microtransactions, they would make little profit.

“I don’t believe they need micro transactions to stay afloat,” said James Kroupa, an avid Fortnite player who has spent more than $4,000 on the free-to-play game. “Any game that’s fun and offers enough free content and stuff alongside the paid content, anything can thrive if made correctly, if developed right.”

The worst offenders with microtransactions are Gacha games, which require players to spend in-game currency to receive random virtual items, often characters. Gacha games lock a lot of their content behind a pay wall, and while yes, you can technically spend hours of your day getting the in-game currency for one pull, there is no guarantee you’ll get what you want. It feels like companies are basically forcing you to spend money to fit the current meta or just to get the character you like the most.

“I think pay-to-win is a big issue,” Kroupa says. “DC Universe Online, they just murdered the game with microtransactions. You have to pay to continue the story. It’s gotten very money hungry–you even have to pay to get certain abilities.”

The point of a free-to-play game is to be accessible to all players, especially those who may not have the finances. When game companies implement these pay-to-win mechanics, they only alienate players. Even if you have more hours on the game, you’re still losing to people who have a bigger wallet than you do.

“Why should free players suffer more than pay-to-play?” Kroupa points out.

Every dollar you send shows companies what we will tolerate. If we want change, then we must hit them where it hurts. Once we stop giving them money, we stop giving them power.

Leave a comment