Don’t picture a blue horse!

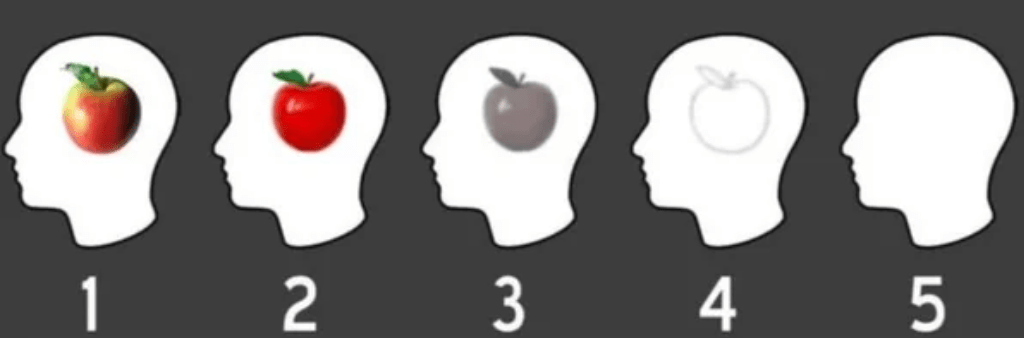

You did, didn’t you? For most people, it would be hard to avoid that intrusive visualization. But for people like me, the estimated 4 percent of the population without the ability to form mental images, that’s simply the default. We have what’s called aphantasia.

My whole life, I’d thought English teachers were using metaphors when they said to “picture” the events of a book while reading. I assumed my exasperation at descriptions of characters’ appearances or of swaying grass was the norm. I saw my struggle to stay engaged as a result of failure on the author’s part rather than my rare incapability to visualize. At the time, I was unaware that aphantasia was even a distinction.

Hard to enjoy Tolkien when you can’t picture Hobbit villages

Outside assigned reading in school, I found myself gravitating mostly towards nonfiction. When I delved into fiction, the pattern involved novels that focused on character arcs and psychology as opposed to grandiose plots or intricate worldbuilding. My reading consists mostly of philosophy, theology, psychology and pop culture. The fiction on that list is comprised mostly of authors like Dazai and Dostoevsky, whose writing styles are famously introspective.

I slowly began to realize I might be the odd one out after Ruben, one of my best friends and a diehard fan of Lord of the Rings, recommended the series to me. I took my time with The Hobbit, remaining engaged mostly by aspects like Bilbo’s inner conflict between remaining comfortable versus embracing adventure.

But upon starting The Fellowship of the Ring, I grew mentally exhausted and put the book down within the first 10 pages. After that, I tried twice more to give it a fair chance and reach the meat of the book. I got no further than the first 30 pages. The interminable exposition, worldbuilding and imagery made it feel like my brain was melting. Even with all my hard work, I simply could not process any of it. No offense to Tolkien; maybe I’ll try again someday.

However, that was only one piece of the puzzle. I knew for a fact I could not get through books of that kind, but I had no idea why. Soon after giving up on Lord of the Rings, I was recommended a list of theology books. After effortlessly finishing five of them back to back, I noticed the difference would lie in the kind of mental work I had to do in order to grasp the book’s contents.

I’m undoubtedly unable to picture the property lines in Hobbit villages, but I can easily comprehend how dissecting the etymology of the original texts of the Bible adds nuance that gets lost in translation. I specifically recognized the ease with which I could digest books that tell more than they show. This realization was key to understanding the strengths and weaknesses that aphantasia has given me as a reader.

I still feared it might be a matter of personal pickiness, until I talked about it to other aphants.

“I do also find myself generally avoiding fiction as a genre altogether, as I’m not able to escape into a book the way some of my peers can,” my friend Spencer said. “I really like to read and am very against writing off an entire genre, especially something that vast, but I can’t get past that it seems harder for me to enjoy it than it is for everyone else.”

Another aphant friend, Maya, said, “I think that’s partially why I never read fiction, because I can’t actually picture it in my head. A lot of the stuff I’m reading is just basically in one ear and out the other.”

Visualization gap doesn’t prevent me from describing

For creating as opposed to consuming, oddly enough, I’ve had writing recognized in the past specifically for descriptiveness. From the rat scurrying over the protagonist’s shoe in a third-grade haunted house story to fight scenes in old, now-deleted fanfiction, it’s not that the visual aspects of a story don’t cross my mind.

You see, there is a bizarre detachment; I cannot put myself in the protagonist’s shoes or see myself walking in that haunted house. I cannot watch that rat scurry over my foot. I can, however, ask myself what might usually happen in the general scope of the idea I am writing about, narrow down what fits the more specific setting or theme, and decide from there what sounds the most attractive, mysterious, or overall finest fit.

It’s time-consuming and often gives me the feeling that my creativity is tremendously limited when writing fiction. It can make it feel like my writing voice is somewhat stilted.

Writing more objectively comes considerably more naturally. Essentially, all I need is a grasp on what it is that I’m writing about, why I’m writing about it and where to go with it. That, and maybe some caffeine and a good playlist.

Despite being able to acknowledge my own limitations, I hadn’t realized the extent to which visualization enhances creativity for other people. An avid reader, writer, artist, and award-winning filmmaker, my friend Michelle has the opposite experience to me; she has hyperphantasia, visualization that is as vivid as real seeing.

“When I write, I see it as a movie in my head. I can change out the actors, I can change out the scenery. A lot of my description comes from seeing it in my head and then talking about what I see,” she said. “It’s more like I’m directing and talking about the movie I’ve made. My writing is very contingent on what I see in my head.”

Making connections between aphantasia and the unconventional aspects of my reading and writing led me to realize how it has impacted other areas of my life. While reading up on psychology, I learned about mindfulness practices. An overwhelming number of them rely on visualization, and I thought the uselessness of those techniques for me was simply personal preference. My opinion at the time was that they were illogical.

The mind’s eye minus the visuals

I’ve never had any sort of affinity or aptitude for visual arts for the most part. Drawing, painting, sculpting and the like are painfully difficult and uninspiring for me. That’s much to my dismay; I greatly admire people with these skills, but I’m self-aware that I would not have the patience to push through the frustration enough to get to a workable level.

Spencer has a similar experience: “I mean, I can put pencil to paper of course, but I feel like there’s this whole hobby locked off from me or made significantly more difficult because I’m unable to visualize anything.”

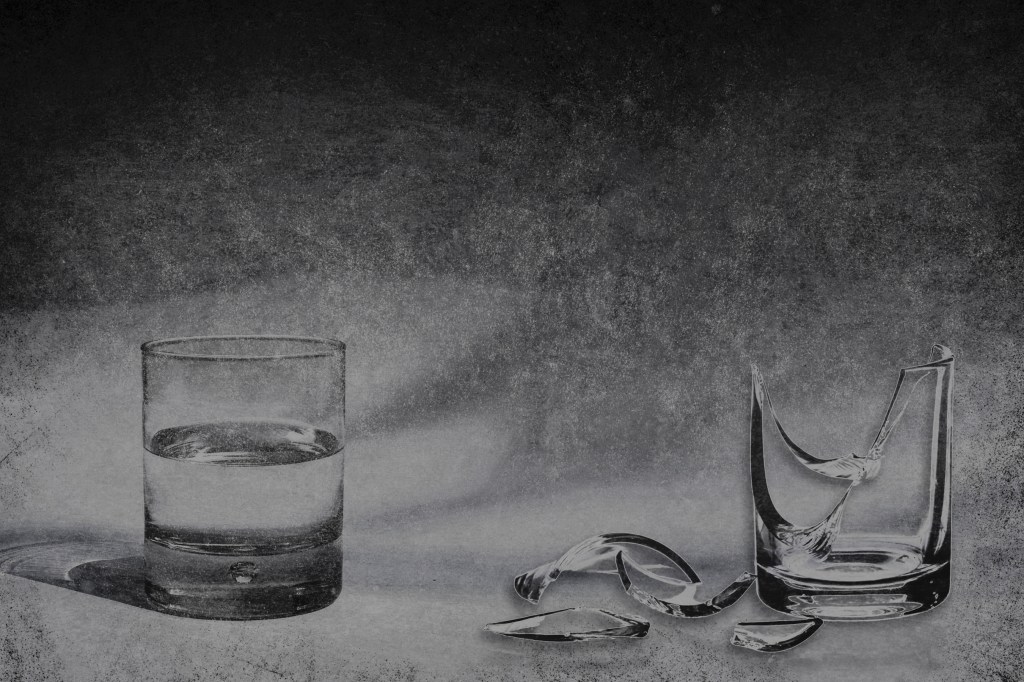

Nevertheless, I greatly enjoyed a high school digital photography class and I love taking pictures. I use Snapchat for the sole purpose of capturing memories. I can’t conjure up the image in my memory of a concert; I can only relive it when I watch the videos of my favorite songs and look back at the pictures I took of the venue. This is quite possibly the most limiting aspect of my aphantasia: it interferes greatly with remembering many parts of life.

However, hyperphantasia can impact memory negatively as well. “When I think of something and I’m recalling it, I remember what it looked like. That’s why sometimes I feel like I get details wrong about things, because I can so easily change it in my head. Was that blue or was that purple? I can see both; I don’t know what it actually was,” Michelle said.

Ultimately, aphantasia enables me to take a step back, for better and for worse. Although I’ve always envied people who can picture things, mental images can be intrusive and overwhelming, interfering with memory and creativity in their own way.

Without aphantasia, I doubt I’d be able to break down my favorite books and form my ideas in the same way, and I’m not sure if I’d want to sacrifice that. I’ve come to understand that aphantasia influences a lot of perspectives I might not otherwise be able to comprehend or hold.

Maybe it’s a good thing I can’t picture the grass being greener on the other side.

Leave a comment